The unique culture was quickly buried beneath successive layers of Greek, Roman and Arabic tradition, and all knowledge of Egypts glorious past was lost. Only the decaying stone monuments, their hieroglyphic texts now unreadable, survived as silent witnesses to a long lost civilisation.

To emphasise the point, University Egyptology courses are full to bursting, and night school classes are attracting increasing numbers of people happy to spend their leisure hours studying the far distant past. This obvious interest has become self-fulfilling. Publishers and television producers are happy to invest in ancient Egypt because they know that there will be an appreciative audience for their work, and every new book, each new programme, attracts more devotees to the subject.

They hold the key to understanding the structure of Egyptian society.

Some 2,000 years on, however, the ancient hieroglyphs have been decoded and Egyptology – the study of ancient Egypt – is booming. At a time when Latin and ancient Greek are rapidly vanishing from the school curriculum, more and more people are choosing to read hieroglyphs in their spare time. And the Egyptian galleries of our museums are packed with visitors, while the galleries dedicated to other ancient cultures remain empty.

There has long been a fascination in Britain with the world of ancient Egypt. What is it about this mysterious civilisation that so catches the imagination?

Their eviscerated, dried and bandaged bodies were once regarded as useless curiosities to be unwrapped, stripped of their jewellery, then discarded, and the archaeological literature is full of horrific stories of unwanted mummies being burned as torches, ground into pigment, processed into brown paper and even dispensed as stomach medicine for the rich and gullible.

The Nile, and the rich land on either side of it©Egypts rich material legacy is the result of her unique funerary beliefs, which, combined with her distinctive geography, encouraged the preservation of archaeological material. The River Nile flows northwards through the centre of Egypt, bringing much needed water to an otherwise arid part of north-east Africa.

Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamunby TGH James (Kegan Paul, 1992)

…full of horrific stories of unwanted mummies being burned as torches…

Tales from Ancient Egyptby JA Tyldesley (Rutherford Press, 2004)

Egypts Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdomby JA Tyldesley (Headline, 2001)

Their total dependence on the River Nile as a source of water and a means of transport had a deep impact on the way that the Egyptians saw the world. Their sun god, the falcon-headed Re, did not cross the heavens in a flaming chariot, he sailed sedately in a solar boat.

All ancient civilisations have contributed in some way to the development of modern society.

Relief showing a woman of ancient Egypt, giving birth. The goddess Hathor, protector of women during childbirth, assists on either side.©The Egyptians were renowned throughout the Mediterranean world for their medical skills, skills that were eventually passed on to the Greek and the Roman doctors that followed them. Unlike those of other ancient societies, the Egyptians were experienced in dissecting corpses because, believing that their souls needed an earthly body, they preserved their dead as mummies.

But, by no means everything about ancient Egypt is fully understood. This lack of certainty over some issues simply adds to the subjects appeal. There are enough unanswered questions – How were obelisks raised? Who was Nefertiti? Where is the lost capital of Itj-Tawi? What exactly are the curious fat cones that lite Egyptian party guests wore on their heads? – and enough published reference books, to allow every Egyptologist, amateur or professional, the hope that he or she might one day solve one of the many outstanding puzzles.

Today attitudes to the long-deceased have changed and it is no longer considered appropriate to destroy a mummy out of mere curiosity. However, the countless mummies, already unwrapped, stored in the worlds museums and universities offer an incomparable source of ancient human tissue. The Manchester Mummy Project, led by Professor Rosalie David, has worked in close conjunction with Manchester Universitys medical faculties to develop a multi-disciplinary methodology for the examination of ancient human remains.

This wealth of objects, of course, creates a highly biased collection of artefacts. The lives and possessions of the poor are under-represented, and we can never be certain that the goods so carefully provided for the dead were representative of the goods used in daily life. Nevertheless, the contents of Egypts tombs, supplemented by the illustrations on the tomb walls, have allowed specialists to develop a greater understanding of Egyptian material technology than of any other ancient civilisation.

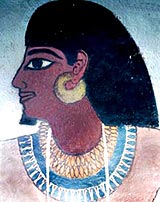

Tomb painting of dignitary of ancient Egypt©Our fascination with ancient Egypt is, to a large extent, a product of the vast amount of material information available. We know so much about the daily lives of the ancient Egyptians – we can read their words, meet their families, feel their clothes, taste their food and drink, enter their tombs and even touch their bodies – that it seems that we almost know them. And knowing them, maybe even loving them, we feel that we can understand the very human hopes and fears that dominated their lives.

Eric (voiced by Daniel Roche) visitsRoman Britain, where he lives a life of privilege.

The Oxford History of Ancient Egyptby I Shaw (Oxford University Press, 2000)

So far we have considered a series of worthy reasons why ancient Egypt is important to the modern world. Egypt offers inspiration, stimulation, valuable knowledge and an insight into our own modern culture. One very important reason, however, has been overlooked. The study of Egyptian art, of genealogy or hieroglyphs, is above all, however, the greatest of fun.

The Egyptologists have noted that both ancient and modern bilharzia infection can be identified by testing for the presence of antibodies. This suggests that the parasite has remained fundamentally unchanged since ancient Egyptian times. It is hoped that the study of bilharzia worms discovered in mummies may eventually help determine those parts of their genetic code that cause the development of cancer.

Valley of the Kingsby J Romer (Michael OMara Books, 1988)

The Great Pyramid, on the Giza plateau©Egypts magnificent stone buildings – her pyramids and temples – have inspired innumerable artists, writers, poets and architects from the Roman period to the present day. The pyramid form, in particular, still pays an important role in modern architecture, and can be seen rising above cemeteries and innumerable shopping centres, and at the new entrance to the Louvre Museum, Paris.

Parallel to the Nile on both banks of the river runs the Black Land – the narrow strip of fertile soil that allowed the Egyptians to practice the most efficient agriculture in the ancient world. Beyond the Black Land lies the inhospitable Red Land, the desert that once served as a vast cemetery, and beyond the Red Land are the cliffs that protected Egypt from unwelcome visitors.

This wealth of objects, of course, creates a highly biased collection of artefacts.

Some of these myths passed from Egypt to Rome, and have had a direct effect on the development of modern religious belief. Reading and understanding the ancient stories allows us to abandon our modern preconceptions, step outside our own cultural experiences and enter a very different, life-enhancing world.

Their work has not only provided a wealth of information about the health of the ancient Egyptians, it has provided useful information to scientists engaged in the struggle to eliminate the parasitical infestation bilharzia (schistosomiasis) which still plagues the Nile Valley. In its worst, untreated form, bilharzia can lead to the development of cancer.

Travel back in time toAncient Britainand create your own stone circle.

But the pyramids are more than mathematical puzzles. They hold the key to understanding the structure of Egyptian society. The pyramids were built, not by the gangs of slaves often portrayed by Hollywood film moguls, but by a workforce of up to 5,000 permanent employees, supplemented by as many as 20,000 temporary workers, who would work for three or four months on the pyramid site, before returning home.

Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilizationby BJ Kemp (Routledge, 1989)

Ancient Egypt: The Great Discoveriesby N Reeves (Thames and Hudson, 2000)

All ancient civilisations have contributed in some way to the development of modern society. All therefore are equally deserving of study. Why then do so many people choose to concentrate on Egypt? What does the culture of ancient Egypt offer the modern world that other cultures – those of Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, or China – do not?

Those who have been bitten by the Egyptology bug cite a variety of reasons for their addiction – the beauty of the art, the skill of the craftsmen, the intricacies of the language, the certainties of the priests – or even a vague, indefinable feeling that the Egyptians came as close as is humanly possible to living a near-perfect life. Individually these would all be good reasons to study any ancient civilisation. Combined, and tinged with the glamour bestowed by some of the worlds most flamboyant archaeologists, they make an irresistible package.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.

Some of these myths passed from Egypt to Rome, and have had a direct effect on the development of modern religious belief.

Five thousand years ago the chain of independent city-states lining the River Nile united to form one long, thin country ruled by one king, or pharaoh. Almost instantly a highly distinctive culture developed. For almost 30 centuries Egypt remained the foremost nation in the Mediterranean world. Then, in 332 BC, the arrival of Alexander the Great heralded the end of the Egyptian way of life.

The original pyramids serve as a testament to the mathematical skill of the Egyptians, a skill that stimulated Greek mathematicians, including Pythagoras, to perfect their work. The Great Pyramid, built by Khufu (Cheops) in 2550 BC, for example, stands an impressive 46m (150ft) high, with a slope of 51degrees. Its sides, with an average length of 230m (754ft), vary by less than 5cm (2in). Higher than St Pauls Cathedral, the pyramid was aligned with amazing accuracy almost exactly to true north.

Chronicle of the Pharaohsby P Clayton (Thames and Hudson, 1994)

BBC © 2014The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

Preserved in their writings and coded into their artwork the Egyptians asked, and answered, the questions that all societies ask. What happens after death? How was the world created? Where does the sun go at night? Lacking any real scientific understanding they answered their own questions with a series of myths and legends designed to explain the otherwise inexplicable.

The bureaucracy that we know lay behind this operation is staggering. Not only did the workforce have to be summoned, housed and fed, but administrators also had to coordinate the supplies of stone, rope, fuel and wood that were needed to support the building work. Pyramid studies confirm that a pre-mechanical society can, given adequate resources and the will to succeed, achieve great things. Pyramid building would have been impossible without strong government backed up by an efficient civil service. No wonder many archaeologists believe that, while the Egyptians undeniably built the pyramids, the pyramids also built Egypt.

The Cultural Atlas of Ancient Egyptby J Baines and J Malek (Facts on File Inc, 2000)

The study of Egyptian art, of genealogy or hieroglyphs, is above all, however, the greatest of fun.

The Complete Valley of the Kingsby N Reeves and RH Wilkinson (Thames and Hudson, 1996)

Believing that the soul could live beyond death, the Egyptians buried their dead in the Red Land, with all the goods they considered they would need in what they thought of as the afterlife. While their mud-brick houses have dissolved and their stone temples have decayed, their desert tombs have survived relatively intact, the dry conditions encouraging the preservation of such delicate materials as plaster, wood, papyrus, cloth, leather and skin.

Author and broadcaster Joyce Tyldesley teaches Egyptology at Manchester University, and is Honorary Research Fellow at the School of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, Liverpool University. She is author ofTales from Ancient Egypt(Rutherford Press, 2004) andEgypt: How a Lost Civilization was Rediscovered(BBC Publications, 2005), written to accompany the BBC TV series of the same name.